This Holy Week, and on this Good Friday especially, there’s one dish that’s undoubtedly gracing the dining tables of Filipinos: binignit.

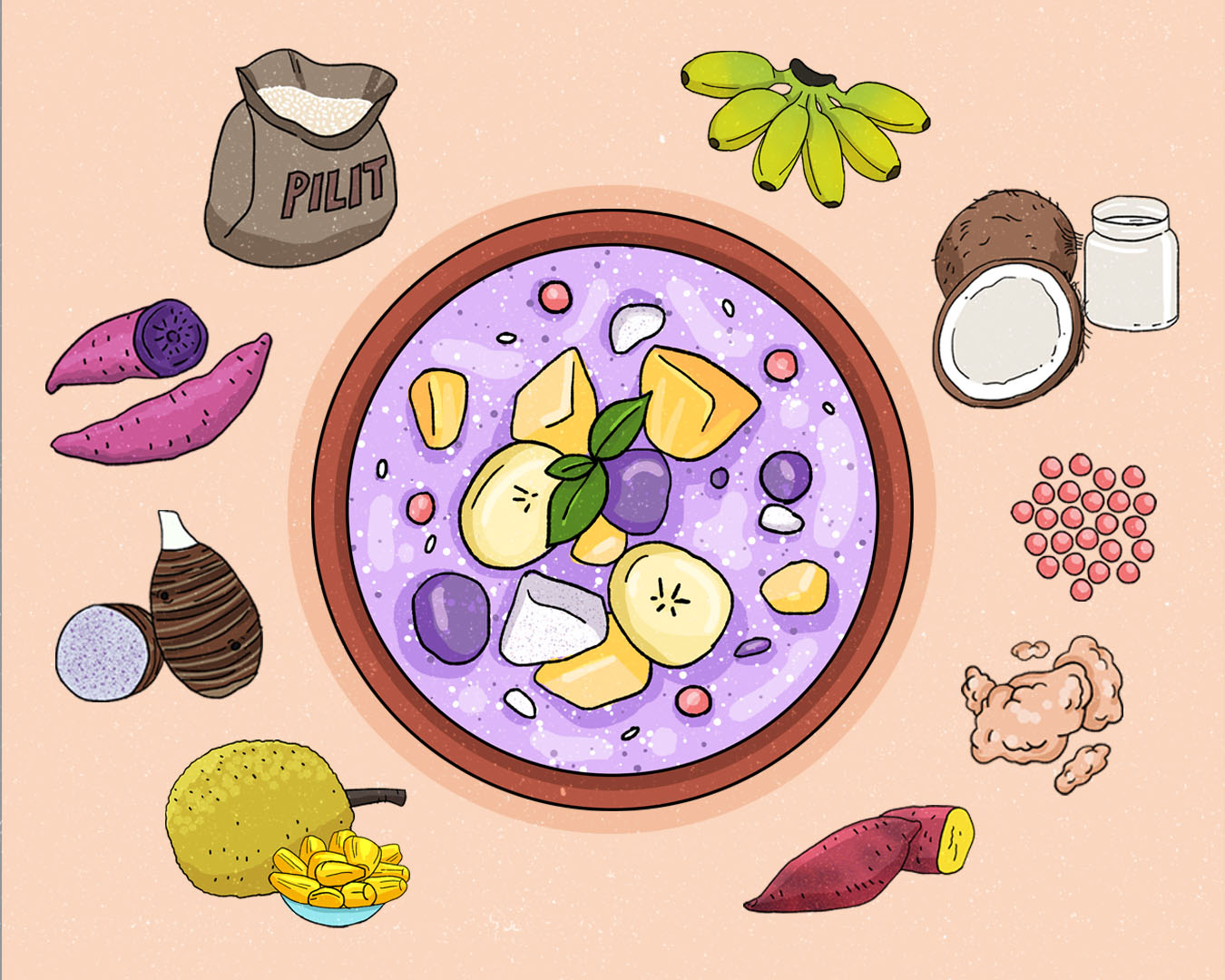

For those observing Good Friday, binignit has become a staple as a hearty meal on a day of fasting and abstaining from meat. Specifically originating in the Visayas, the dessert soup can be served hot or cold and is made of different tubers, fruits, and coconut milk—all of which factor into its distinct appearance: a purple mishmash of colors, shapes, and textures.

In the interest of staying honest this Lenten season, I confess: I’ve never eaten binignit before. Growing up, I was not the most adventurous of eaters, so every year, when I came across the strangely colored and soupy concoction, I would pass.

Today, my extended family continues to enjoy Nora’s binignit every Holy Week. Nora is practically family to us as she takes on my great-grandmother’s binignit recipe.

In many ways, binignit is a symbol of tradition. Different families have passed on different methods for cooking this dish, and each one of them tells a unique history of the people who would sit down together to eat it. This is Nora’s.

Nora’s Binignit Story

Every person I know claims that someone in their family makes the best binignit, and we’re definitely no exception. My aversion to unusual food aside, I knew Nora made binignit that my family would look forward to and rave about every year. “Nor, kanus-a ka mag himo’g binignit?” (Nor, when are you making binignit?) would become a common question during Holy Week. Even during the peak of the pandemic, she and my aunt had some delivered to all of us.

So it was only fitting that I would come to her to figure out how to make it. I watch Nora flit through the same kitchen she’s been cooking in for decades, where she would cook adobo, another one of her dishes that always brings our twenty-strong family under one roof in anticipation.

I ask her if she’s been eating binignit all her life, and she responds with a slightly incredulous look. She tells me how, as a young child, she learned how to harvest landang, the native tapioca that goes in the dish. She would spend her Lenten season felling Buli palm trees with her family in Borbon—another tradition passed down. She goes on to describe the laborious process, which usually takes days of hard work. For brevity’s sake, I won’t walk you through it, but I can assure you, it’s much more tedious than you would think.

The painstaking harvest of landang made it all the more special to Nora’s family and their community. “Sometimes we would even have binignit with just landang in it,” she says in Bisaya. Since living with our family, though, she has stuck to the recipe from my great-grandmother.

How to Make It

Regardless, landang stays essential in Nora’s binignit. Her first step is to boil the landang (and sago, if you want to) in water until it is softened. From my research, the main component of binignit is actually pilit or glutinous rice flour, but interestingly, Nora doesn’t even mention it in her recipe. If you choose to add pilit, it’s best to add it before anything else.

As the “sinkers” boil, cut your vegetables and fruits, and make sure to keep them in uniform size to ensure they cook evenly. Some of the crops commonly used across the region for binignit include taro (gabi) and/or purple yam (ube), sweet potato (kamote), jackfruit (langka), and saging gardaba (or its close relative, saging saba.)

Once the pilit and landang are cooked, add the fruits and tubers you want to include. Generally, the kamote, gabi, and ube go in first as they take a little longer to cook, with the gardaba and langka going in after the rest have softened up a bit. Stir the mixture constantly to keep all those ingredients from sticking together. Many recipes actually call for all the ingredients to be boiled in coconut water, but for Nora, it comes only after everything has been cooked.

To prepare the coconut cream or milk, grate the meat of a mature coconut and add a little warm water before extracting the cream. This can be mixed with extra water if it’s too thick, but Nora also suggests using the milk from the second extraction, as it’s usually thinner and easier to incorporate into the dish.

Others who aren’t able to (or would rather not) do all that work can opt to buy freshly grated coconut in wet markets to extract milk from. Or, for the shortest of shortcuts, buy canned gata at the grocery store. Whatever the case, add the coconut milk to the pot over low heat. It’s important to keep the dish at a slow simmer, as turning the heat up too high can cause the coconut milk to curdle.

From there, brown sugar, or muscovado is added to taste. As an option, you can also add the first coconut extraction off the heat for a thicker consistency. The finished product is then served hot or kept in the fridge to be consumed cold.

Binignit in More Ways Than One

So how do you make binignit? The beauty of it is that there’s no one way to make it. Everyone will make it a little differently because they learned it a little differently. Households with roots in different provinces use fruits that had been abundant in their area, and many follow recipes from days when entire communities would come together to make it. Even as I asked Nora for her recipe, she didn’t give me any measuring units—it’s all by feel and by preference.

As I think of the countless people making binignit in their kitchens this Holy Week, I find myself in awe. Despite knowing the general process of making it and what commonly goes into it, I wonder: how different is it from the recipe I’ve just learned? How long have they been making it like that? Who did they learn it from?

There’s a Bisaya saying that goes, “Binignit aron malangit.” Roughly translated, this means, “Eat binignit to go to heaven.” While everyone is free to make and eat binignit any time of the year, its association with Good Friday—a time usually spent with family—has given it a strange sort of reverence among the Visayans. This unique dish continues to endure not just as a symbol of faith, but also as a representation of community, family, and culture.