“Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man. For this he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity.”

Everyone on Earth has never known a world without fire, and almost just as many have never known a world oblivious to the knowledge of two other destructive forces of nature, that are far more fundamental than fire: fission and fusion.

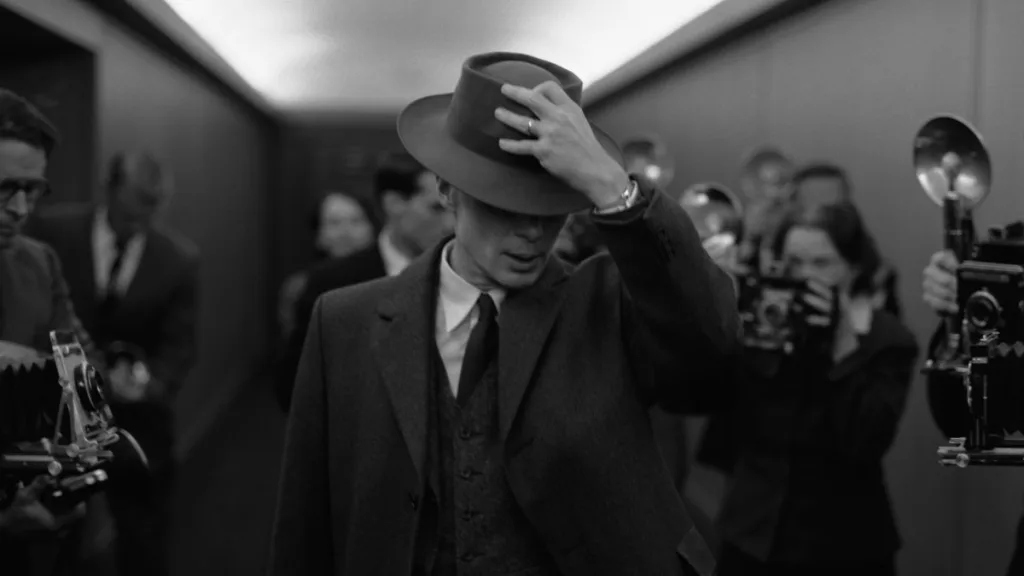

Director Christopher Nolan structures Oppenheimer in interweaving narratives that are aptly titled as such, as we’ve come to expect from his work. But that’s not to say that this kind of structure becomes gimmicky in Oppenheimer– it’s almost eerily perfect for it. These are reactions that create entire galaxies and universes, after all, and Oppenheimer is the Promethean figure who gives humanity the chance to harness such incomprehensible power. Fission and Fusion show us the makings of the bomb– and its ensuing fallout– simultaneously, making Oppenheimer’s desperation to create it all the more tragic as the two parts slam into each other and leave nothing but devastation in their wake.

The film’s overarching theme is one that’s familiar to all of us– things are not always black and white, no matter how much we might want it to be (though Fusion is shot beautifully in IMAX black-and-white film specifically developed for the movie). Dichotomies, false or not, exist everywhere: in nature, in politics, in people. Even Oppenheimer, genius that he is, and a son of Jewish immigrants himself, is not immune to this as he weighs the implications of his impending invention: “I don’t know if we can be trusted with such a weapon, but I know that the Nazis can’t.”

This is the kind of high-stakes morality we see at play in Nolan films frequently, but he’s careful not to paint it as the correct one, if there even is such a thing. (He’s even famously said in interviews that Oppenheimer‘s black and white scenes are objective, while color is subjective, which is a kind of spoon-feeding I would never have expected from him.)

Throughout Fission, we see a young Oppenheimer spearheading the Manhattan Project, bringing together some of the most brilliant Allied minds and convincing them of this cause, all of them with names that are burned into my brain from the trauma of high school physics classes. Oppenheimer sees these atomic forces as a means to ensure peace after numerous years of war. To him, the development of an atomic bomb is just another inevitability, a step towards that future, and it’s only a matter of getting there first.

Matt Damon’s Leslie Groves, a burst of energy in a room full of mostly reserved intellectuals, speaks with more conviction than Oppenheimer does, as he tells these scientists that this is The Most Important Thing to Ever Happen in the History of the World. It’s easy to write a line like this off as blockbuster fodder, but in hindsight, it might just be true.

It’s Schrödinger’s cat, if the cat were really a bomb– before its invention, it’s still simultaneously in the hands of both the Allies and the Nazis. And Oppenheimer is the only one who dares to look inside the box and see. Is the cat dead or alive? Is it going to be us or them? Theory will only take you so far.

There is no wisdom to gain from theory without practice. The young Oppenheimer we meet flirts with communist theory and obsesses over quantum theory and soaks up all the theoretical knowledge he finds in the world. He imagines an entire future of nuclear energy in the infinitesimal space of an atom. Ultimately, he is only given the chance to put his theory into practice under orders to unleash it as a weapon (or ‘gadget’, as he insists.) And even when Germany surrenders and some of the project’s scientists begin to question whether or not such a bomb is necessary, Oppenheimer is adamant that their work continues.

Set nearly fifteen years after the test, Fusion recalls the confirmation hearing of Lewis Strauss as Secretary of Commerce, and though it seems like the Manhattan Project and Los Alamos are a distant memory, its repercussions are only just beginning to shape post-war America and the world. The physicist has fallen from grace, yet his presence and influence continue to plague Strauss and the United States’ interest in advancing the nuclear weapons program, and vice versa. As we cut back and forth between pre- and post-Trinity, it becomes clear: it doesn’t really matter if the cat is dead or not when it’s Pandora’s box you’re opening.

The moments leading up to the opening of that box are filled with high tension, as if we haven’t already been watching its aftermath alongside its inception. Before the test, Groves and Oppenheimer discuss the near-zero chances of igniting the Earth’s atmosphere and destroying the world, echoing a previous conversation with Albert Einstein. Obviously, we know it doesn’t do that, but as we see the weight of the world on these scientists’ shoulders, we can still feel that possibility hanging over our heads, especially now that there are warheads thousands of times more powerful than this gadget, lying in wait in silos all around the world.

The detonation itself is breathtaking, with visuals that quite literally make your heart leap into your throat. Nolan’s insistence on using practical effects makes the explosion so palpable and horrific, demonstrating this very real threat that we know is going to befall hundreds of thousands of people only weeks later. The test goes well– extremely well, and when the town of Los Alamos erupts in celebration, it’s hard not to dread what’s to come.

After Trinity’s success, Oppenheimer has his work taken away, to be dropped on a target that is worlds away from him, and us, the audience. Nolan’s choice to forgo presenting the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings has been polarizing to say the least, but it makes sense– this man of science was only obsessed with making the discovery that would change the world, and he was so short-sighted that he had only ever scratched the surface of the real human (see: not theoretical) implications of his invention. Theory will only– well, you get it.

Instead, we get another meeting of powerful men in a room, arbitrarily discussing where to drop these new weapons, which is even more horrifying to watch. Oppenheimer is helpless as what was once the potential to end wars morphs into a certainty that could end the world instead, at the whim of self-important men like Strauss, and we watch helplessly with him in despair. Mankind is far too short-sighted to wield power they can’t ever really control. Oppenheimer is proof of that.

In an almost liminal narrative, suspended between both Fission and Fusion, we sit in a conference room, witnessing the 1954 hearing to determine whether Oppenheimer would get to retain his security clearance. His staunch opposition to the development of the H-bomb program post-Trinity has made him the target of resentment among politicians, and we see Oppenheimer laid bare (no, seriously), this American Prometheus who was bound to a rock to have his liver eaten by eagles. His left-wing associations, which include a brother and a lover who were members of the Communist Party of the United States, become the subject of scrutiny, as does his erratic behavior with the ominous Colonel Pash (be warned: this particular casting is a jumpscare.)

We watch Oppenheimer get picked apart, sitting by while the choices that he had the burden of making are put on blast. Who would want to justify their whole life? Rumors of espionage in Los Alamos had begun to stain his reputation after a Soviet atomic test of a similar gadget was detected, and in the end, thanks to some reluctant testimony from others who worked on the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer is deemed a security risk, and stripped of his clearance.

Later on, we see Strauss’ role in this, and how his encounters with Oppenheimer had painted a picture in his mind of secretive scientists who believed they knew better than those in power. Robert Downey Jr. is an excellent Salieri to Oppenheimer’s Mozart, as his developing grudge against the latter kicks off its own chain reaction and leads to the disgracing of the physicist. While we experience Oppenheimer as a two-sided coin of naivety and genius, Strauss considers him to be just as conniving, suspicious, and self-important as he reveals himself to be in a startling last-minute display of arrogance almost reminiscent of another Downey role… but I digress.

As the audience, it’s hard to watch a genius like Oppenheimer be so stupidly naive, but we have the advantage of knowing the outcome. Kitty Oppenheimer, played by Emily Blunt who to me almost evokes both Mal and Dominic Cobb in this film, gives us some sense of catharsis as she lambasts her husband and asks him to fight back and see this for what it really is: an effort to vilify him. “Is anyone ever going to tell the truth about what’s really happening here?” Oppenheimer despairs, and we almost feel mournful at such a gross misuse of one man’s intellect, and how quickly he is spurned after his usefulness has run its course, but we also know that Oppenheimer has largely dug this hole for himself, and for us. How could such a genius be so blind?

Forget Schrödinger’s cat. It’s Oppenheimer’s world. We simultaneously destroy ourselves and we don’t. This man bore the burden of giving us this knowledge, yet ultimately it wasn’t even him that decided what it would be used for. The powerful men of the world looked inside that box and saw a weapon to win all wars instead of a way to deter them, as Oppenheimer had once imagined.

And this isn’t to try and minimize Oppenheimer’s role into that of a man whose genius was simply accidentally used to decimate entire cities. If anything it only highlights how heavy a toll that must take on one’s soul, to know he was the catalyst for something so catastrophic. We see Oppenheimer for the coward that he is, as he refuses to apologize publicly despite clearly unraveling under the weight of his actions. This is not the Titan Prometheus, this is a mere mortal.

I remember the man we were introduced to almost three hours ago, who poisoned an apple meant for his teacher and raced through the Cambridge campus the next day to take it back. This time, he can’t snatch back the bomb like he did the apple from Kenneth Branagh’s hand. As Strauss put it, there’s no putting the atomic genie back in the bottle.

After the dizzying chain reactions between Fusion and Fission have reached critical mass in a magnificent climax, we finally slow down and see Oppenheimer’s perspective of his encounter with Strauss and Einstein from the beginning of the film. This moment, which had become an unwitting spark igniting Strauss’ animosity and subsequent sabotage of Oppenheimer’s career, turns out not to have anything to do with Strauss at all.

“Albert? When I came to you with those calculations… we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world.”

“I remember it well. What of it?”

Oppenheimer replies: “I believe we did.”

The benefits of winning a war had once outweighed the minuscule risk of setting fire to the atmosphere. Oppenheimer’s already told us earlier on that he’s no good at math– but this is the same man who made that calculation.

Despite Strauss’ deluded attempt to arbitrarily smear Oppenheimer based on perceived slights to his ego, Oppenheimer’s role in history no longer has a question attached as to whether or not he’s a hero. It doesn’t matter anymore, not with the world up to its neck in nuclear weapons developed by governments, ones run by the men who think themselves equivalent to the gods Prometheus stole fire from.

Nolan loves to give us characters who are cursed with knowledge, but this one man’s knowledge has somehow cursed us all. We watch Oppenheimer stare blankly in horror at the chain reaction he’s caused and its potential to destroy the world, as Nolan treats us to some more brilliant visuals and sound. The end result is a harrowing finale that leaves the audience utterly devastated.

By the time I headed out of the theatre, I was already buying tickets to watch it again. Seeing the film in 70mm IMAX is truly the most immersive cinematic format I’ve ever had the pleasure of experiencing, and more than a handful of times I found myself with my hand on my chest or over my mouth in awe.

I also cannot sing enough praise for Ludwig Göransson’s score, which feels as expansive and desolate as the New Mexico desert, but also as cerebral and rich as the violin that features heavily in it. Can You Hear The Music and Destroyer of Worlds are almost perfectly composed for the film, with otherworldly waves of sound beating against similarly otherworldly visuals, overlapping and increasing in tempo, before culminating into the familiar– but still effective, after all this time– wall of sound we’ve come to expect from any Nolan score.

Oppenheimer also has stellar performances all around– Josh Hartnett in particular is a lovely surprise as Ernest Lawrence– with high-caliber actors in supporting roles, as well as some almost-not-quite-but-just-might-be gratuitous cameos (yes, Gary Oldman, I love you, but I’m looking at you.) The cast makes marvelous work of Nolan’s most densely-packed and calculated screenplay, and leave you hanging on their every word. (Obligatory snaps to David Krumholtz and Benny Safdie, who absolutely cleared in every scene they entered.)

But really, Cillian Murphy is the analogous radioactive core around which this explosive cast– hell, this entire movie– is assembled. His enigmatic performance keeps you entirely captivated for the entirety of the 180-minute runtime, from the moment he’s animatedly lecturing about quantum physics, to when he is crumbling after the weight of his deeds comes crashing down on him in a jarring (and only slightly trite) vision of his cheering audience burning to a crisp in a nuclear explosion. Murphy is the movie, and I fully expect a bevy of nominations coming his way for his achievement next year.

In Oppenheimer, we see Nolan tell a story we already know, without the mind-bending exhilaration of memory loss, black holes, reverse time, and dream architecture. Even Dunkirk has its dogfights and high-powered action. And without all that suspense and preternatural complexity, we see a more raw, mature, if only slightly flawed, direction from him.

Here, Nolan takes a very real event that has completely changed our world, and, with much credit to Murphy, simply paints a devastating portrait of the man who gave us the power to destroy ourselves. Despite its apparent scale, spectacle, and stakes, and while arguably not Nolan at his quote-unquote best, Oppenheimer is, in my opinion, the most thoughtfully written, intimate, and poignant work we’ve seen from him thus far.

Photo courtesy Universal Pictures

One thought on “Destroyer of Worlds: Oppenheimer is An Astounding Display of Horror and Beauty”