Ten years ago, I had the paralyzing sudden fear of death. It came after my doctor told me that my leg was not broken at all in any way, but, in fact, had a bone tumor—the official diagnosis was osteosarcoma. I was thirteen years old, just fresh inside the forest of puberty. It was the beginning of my young life, but it was possibly also the end. My doctor immediately wanted a biopsy to check if the tumor was cancerous or not. It was my first surgery and I thought to myself that it was already malignant—I wanted it over with. I wanted to confront cancer right away, head-on like a freight train. When my family found out, they were devastated; even more so when the disease started to reveal itself. I was right; death was on my doorstep and he knocked like a motherf****r.

During this time, I also was starting to have these feelings regarding my sexuality, which were flowering feverishly. I always thought that I was attracted to the opposite sex, but an encounter with a boy from my high school unraveled my journey. I didn’t understand what those emotions were, but I knew they were essential feelings. It was as though a corpse floated up to the surface of the still pond of my unconscious. It rippled throughout my whole body—I could feel everything when I looked at this boy. I had hysterical thoughts about him like I was possessed. It awakened something in me that was always there, but it just wasn’t fully realized. The only way I can explain it is if I recall a dream I had when I was five—men were hanging upside down, naked. It wasn’t an erotic picture to me; it made no sense to me at that age. To the mind’s eye of a child, it was a figurative scene floating in the ether.

Is this how puberty works?

The next two years after my diagnosis was a hell hole. Chemotherapy, surgery, medication, syringes. Loneliness, isolation, trauma, fear. This was probably the worst way to go through puberty but strangely, it felt cathartic and necessary. I went through a ritual of blood and pain for me to reach my true authentic self. It was life’s way of hazing me before I go down inside another circle’s unforgiving spiral. I felt like a rotting piece of meat inside the hospital. I could see death moving so fast like flickering bright lights.

To add to the whole chaos of this, I had to come to terms with my sexuality at this excruciating time as well. And believe it or not, even with cancer, I was afraid of this. I was afraid of myself; I was afraid of the real truth coming out. I was afraid of death and I was afraid of living my life as a gay person. Even though my mind was more open now than before, my negative preconceived notions about homosexuality were stronger. I felt as if society would crucify me and stone me to death for being myself. The last stage of my metamorphosis was the amputation—my cancer-ridden leg had to be hacked off so I could continue living my life. I would say it was a cathartic experience; from then on, I felt nothing worse could ever happen to me.

The personal is the political, and it was all personal to me.

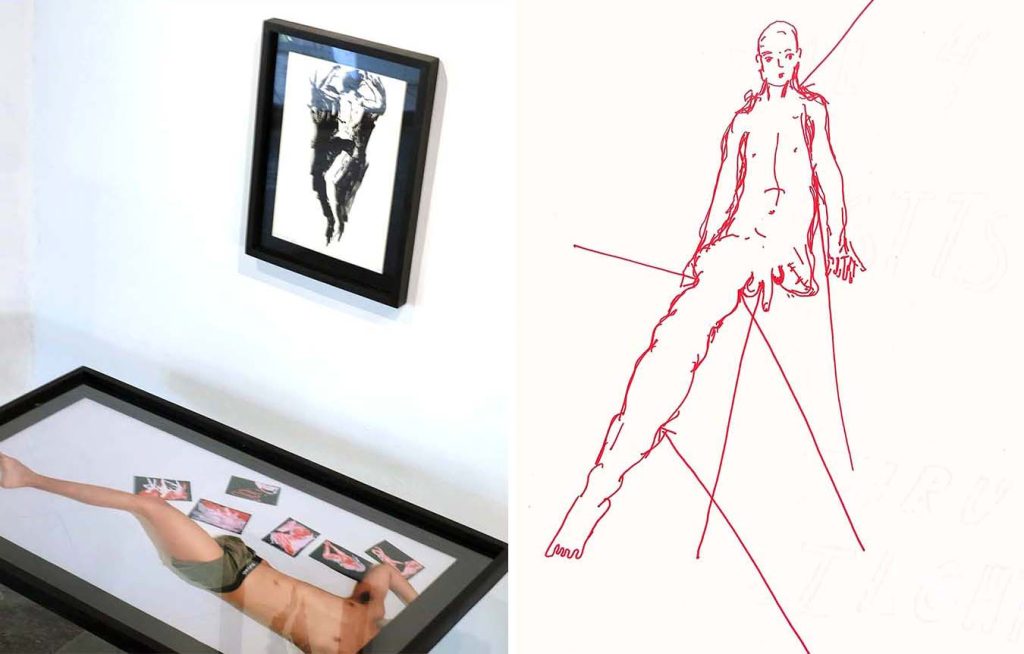

When I address ableism, I must first undergo a myopic introspection, analyze myself as an artist would, and ask the important questions about the universal basic rights of a human being. Am I being treated fairly like any other normal person on the street? The only way I can dissect this discrimination is to recognize my personal life and expand it into the political, so this is where I make my work. I started to make art as a way to pass the time, I had nothing else to do but recover after I went into remission. I started to learn how to play the piano, guitar, and then poetry. The next thing was art, which opened up another facet of my maverick life. I had the gift of analysis through the visual. But it all started to go full circle once I conjured up ultimate sublimation, the true privilege of the artist, in realizing that the work was immaterial. It didn’t matter what I made—it had to respond to my emotions and my thoughts during the present moment. The physical work was unimportant—what mattered more was the idea and the context of the piece. Brancusi once said something similar, and I quote, “Things are not difficult to make; what is difficult is putting ourselves in the state of mind to make them.”

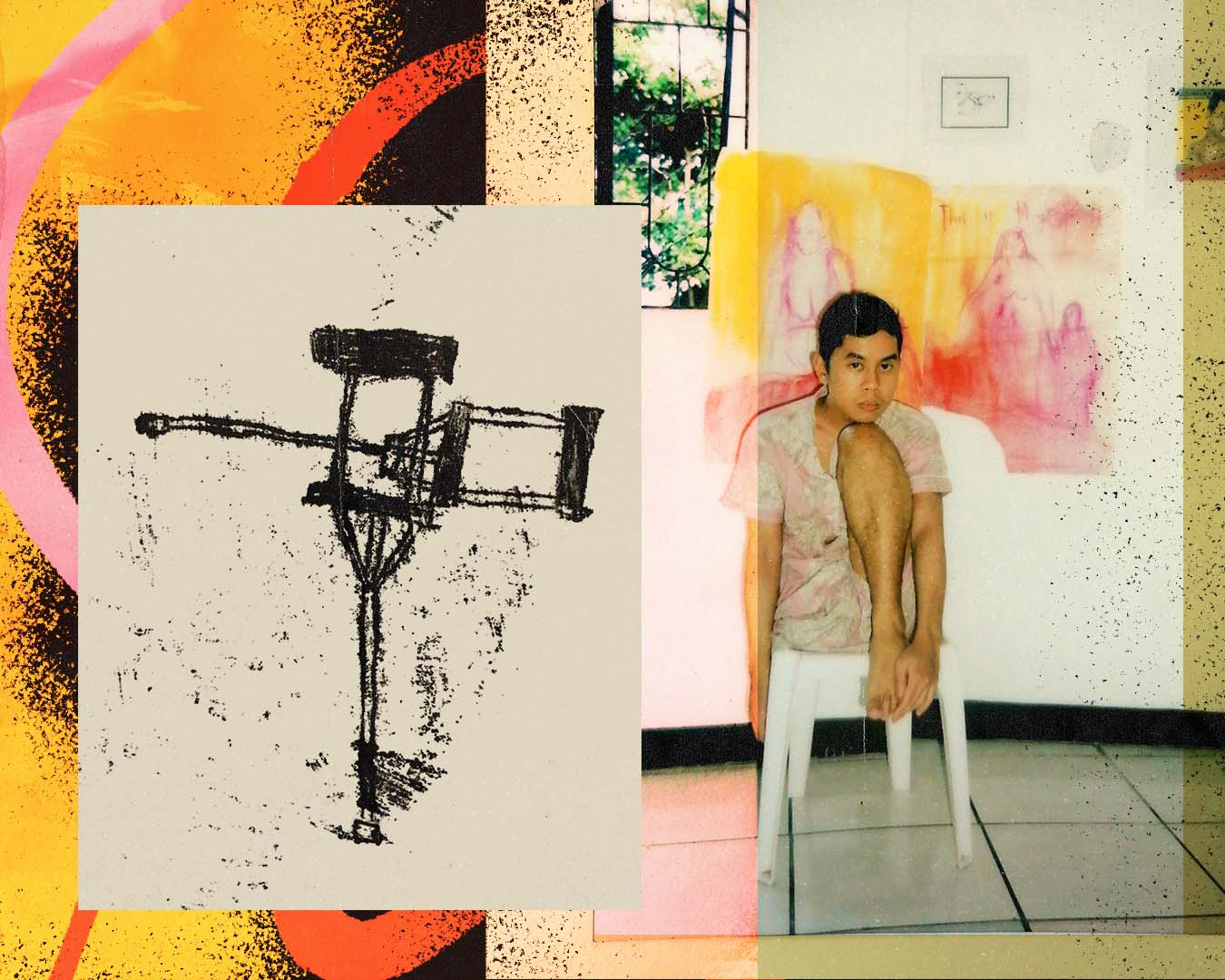

In A Thousand Years by Christian Ray Villanueva

In 2020, for the Jose Joya Awards – I made a mixed media piece titled In A Thousand Years as a protest against the green movement for not being more inclusive toward disabled people. It was about my internal struggle. I screamed from the top of my lungs: include us in your emergency plans during climate disasters, incorporate us in your objectives when it came to everyday disposables (e.g straw, plastic bags), and provide us overall with more accessibility. It expanded the conversation on disability to the climate movement in general. For example, is it fair that the masses are sometimes held more accountable than the corporations who are fuming their toxic waste in the very air we breathe?

Who do you think you are?

The very systems in our society that are in place are inherently ableist and homophobic. I feel very punk rock about this—as an artist, you have to be radical with your ideas, and not just think about commercializing yourself, for God’s sake. Art is beyond money and recognition! Art gives us the privilege of dipping our proverbial toes into the unknown, asking questions about our very nature as human beings, and having the potential to predict the future. I feel grateful to be an artist, and I feel lucky to have this tool of self-discovery. Art serves a purpose in my life, and that is therapy and sublimation. But, I’m very ecstatic to say that it has brought awareness to some issues that can be considered underrated. It becomes a symbiosis: art provides a bridge of exchange and a higher level of communication. A work of art does not have to be explained; it is not my job. The work has to resonate with the audience for it to be fully realized. If it doesn’t achieve that, then I have failed in my vocation. But really, the more important question is: does art have the capacity to change the world and the systems in place that have fostered these hurdles for people like me? I doubt it. I don’t believe in this brand of heroism when it comes to being an artist, nor do I see our way of living as all too important. I believe that people, in general, can tap into this power to break down these oppressive structures of brutal tyranny. We need our voices to be as loud as they can be in demanding our freedom from those who try to take it from us.

The “The Vessels of Time” exhibit curated by Christian Ray Villanueva is opening on August 4, 2022 at the High Space, located at Qube Gallery, The Crossroads. Follow Christian and Qube Gallery on Instagram.

Photos and art courtesy of Christian Ray Villanueva

Thank you, Christian for the art you give to the world. I like the vividness of your art and this was mirrored in the first part of this written piece where the use of literary devices was visceral and livid. I feel it is there that your artistic power lies.