Considered to be one of the most influential pieces of art of the Romanticism art movement, Eugene Delacroix’s 1830 painting “Liberty Leading The People” shows a woman dressed in a toga-adjacent piece of clothing, with her breast exposed, and a cap typically worn by freed slaves charging forward amidst a battlefield, leading her followers to victory.

Between the woman in “Liberty”, the literal Statue of Liberty in New York, and countless other works of art depicting women as harbingers of freedom, it is no secret that women are effective symbols of empowerment. However, despite the widespread depiction of women as symbols of liberation, it is ironic that women are still experiencing oppression and marginalization on a global scale. In fact, women in France weren’t even allowed to vote until more than a century after Delacroix’s “Liberty” painting.

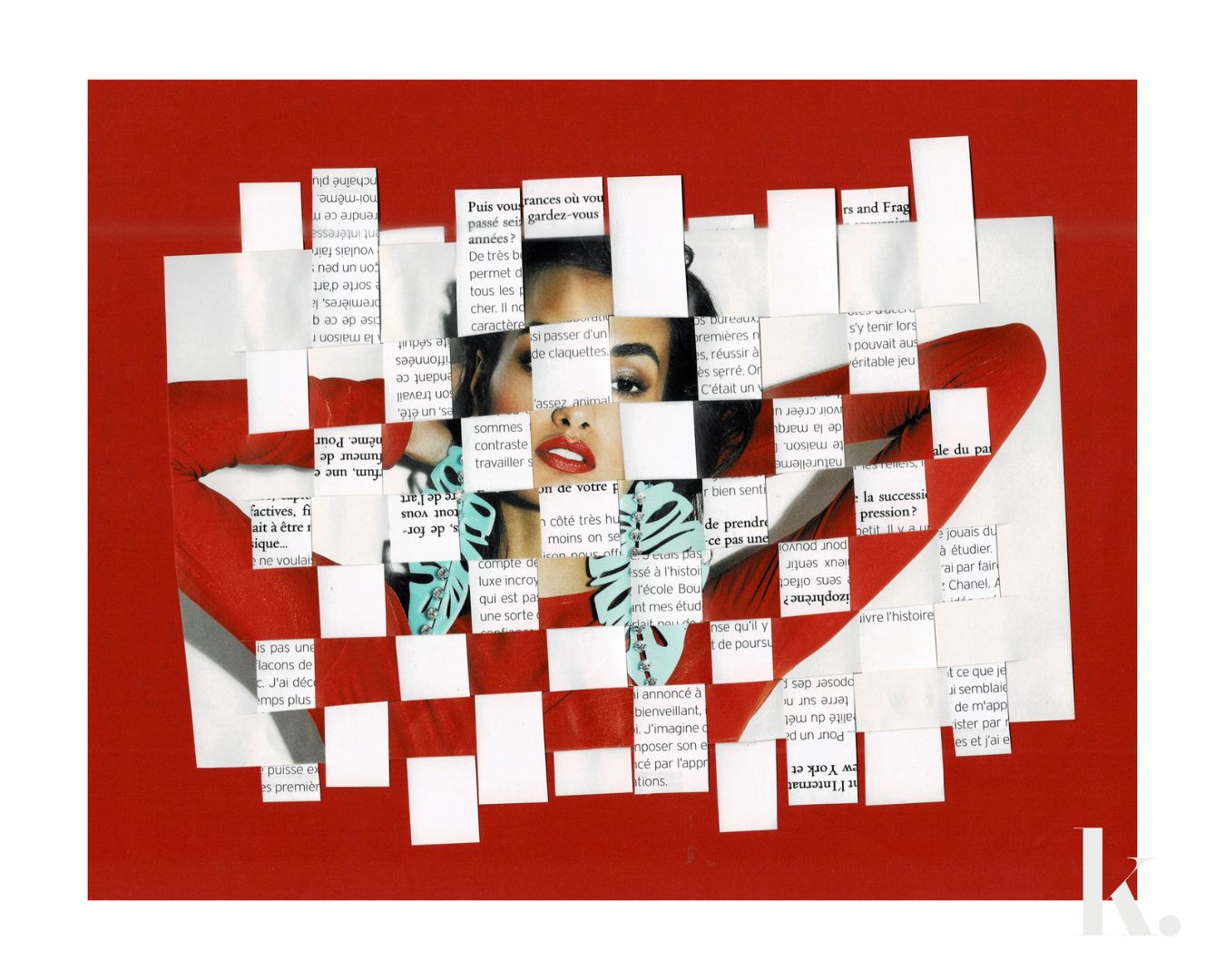

“Three Figures of the Self” by Belle Maurice

These are the musings I tell my friend Victoria as we walk across the UP Cebu campus on one humid afternoon. We recalled our art classes in senior high school, remembering how “Liberty Leading the People” was one of the paintings we were asked to study. “Artist or not, you’ll surely recognize that painting,” Victoria says. Music lovers would definitely agree— “Liberty” is the cover art on Coldplay’s 2008 album, Viva la Vida.

I told her about my observation on the phenomenon of women as “muses of freedom” and how this goes further than art— we see this in fiction, popular culture, even in current events. I started listing down names until I had to catch my breath while walking: Katniss Everdeen, Atty. Leni Robredo, Maria Clara, Greta Thunberg, Frida Kahlo, SOPHIE, Maya Angelou, Malala Yousafzai, Michelle Yeoh. My guess is any woman who excels in a particular field is lauded for their achievements, and is, at least for a period of time, considered a beacon of hope for everyone else despite not having the intention to become this in the beginning. Regardless, the woman is put on an impossible pedestal of absurd expectations. Is this an inevitable fate for any woman who excels?

“I Was Born into the Arms of Five Virgin Marys” by Chanel Pepino

I began to wonder what true freedom looks like for women in art. “Being able to do art freely means being able to be seen without sexist judgment,” Victoria tells me.

“I want to be able to create without the pressure of having more to prove because I am a woman.”

Victoria and I had just perused the current exhibition at the Jose T. Joya Gallery which was entitled “Paperworks”, a gallery show that featured works by UP Cebu art professors. The gallery note, curated by artist and professor Ivy Marie Apa, says “Authority emancipates when it is self-reflective and self-critical,” highlighting the importance of self-critique in the study and creation of art.

I asked Victoria if creating art makes her feel liberated. “It actually makes me feel more restricted,” she says. “Women are just as capable of creating art that are as good as men, but it always seems like we are judged first because of our gender. It is exhausting to feel like we always have something to prove, as if we’re not critical enough of ourselves.”

“Gintong Kanopik” by Victoria Tanquerido

The poet and Filipina revolutionary Lorena Barros once wrote this passage about the new Filipina woman: “She is a woman who has discovered the exalting realm of responsibility, a woman fully engaged in the making of history.” However, it is unfair to assume that every woman intentionally wants their work to be symbolic, meaningful, or historical. Society doesn’t put cis men’s work on that same pedestal.

But Victoria, along with many other women artists, still loves creating art despite the gendered drawbacks that come with it.

“I love being called a woman sculptor,” Victoria tells me. “I don’t know if I can align myself with any art movement or art style but I’ve always felt the belongingness in being identified with women.” I work with Victoria in a foundation called the Drawing Class, an initiative focused on democratizing the study of art for anyone in Cebu who wants to learn how to draw. The other purpose is to create an all-inclusive space for artists to connect regardless of educational or artistic background.

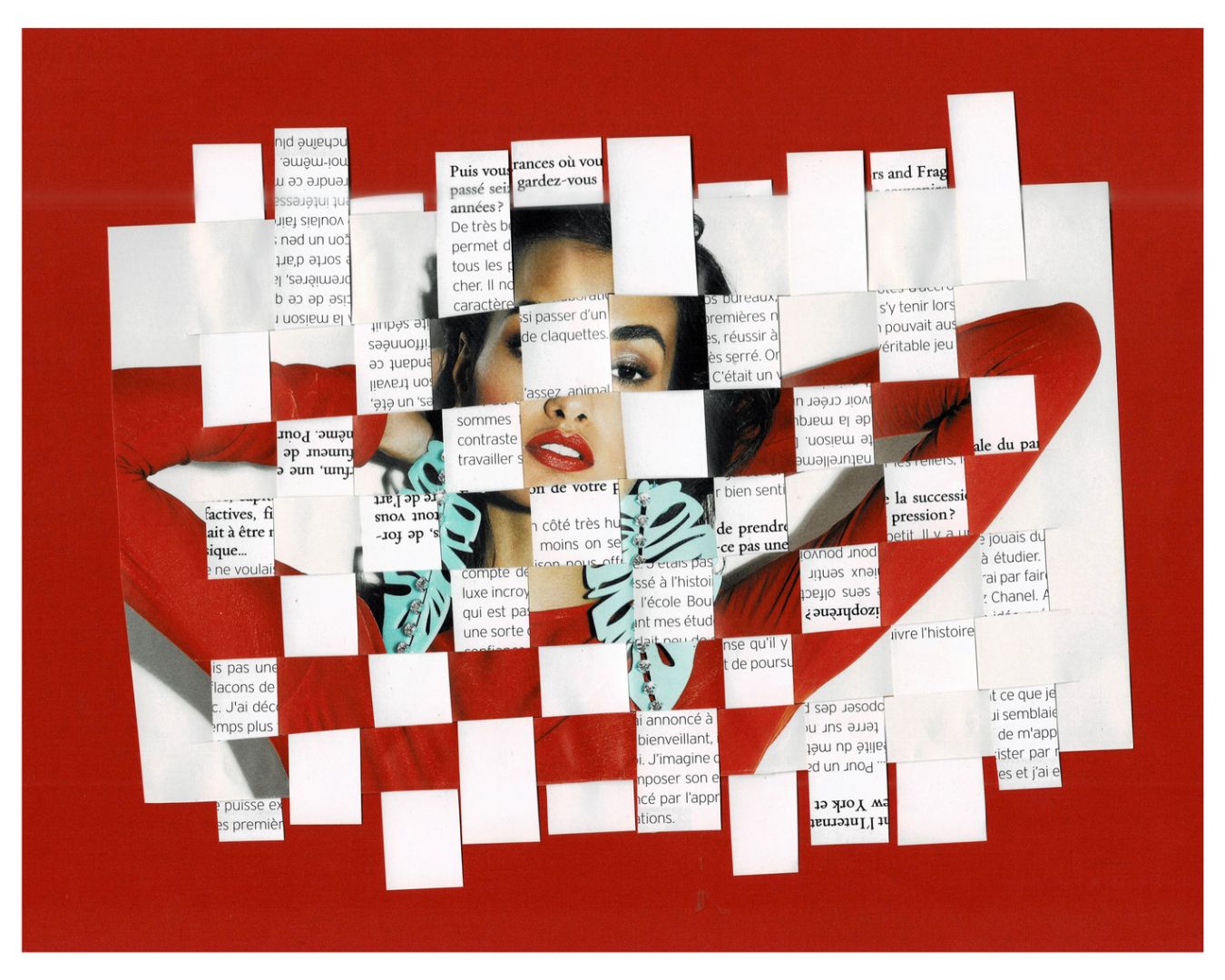

“Visual Miscommunication” by Celine Lagundi

Victoria, who is also Joya Gallery’s current Head of Gallery Operations graciously gave me relevant information about what it’s like to manage a gallery behind the scenes, as well as her experiences as an ingenue.

“Going into college, I realized how male-dominated the art scene really is, especially the practice of sculpture.”

She laments the “forced diversity” in gallery exhibitions, in management roles, and in the art scene in general. In these spaces, the goal is “representation”— it’s an “all-female exhibition”, a “woman-led collection”, a “female-prioritizing space” with little to no regard for anything else.

(From left to right) “Self-Portrait”; “Drunk Self Portrait”; “Eye on the Prize” By Chanel Pepino

That’s not to say having these spaces are not positive breakthroughs. But with the progress the feminist movement has achieved in the past century, the time feels right to veer away from mere symbolism and shallow representation to move forward to actively demanding for a better, safer, more inclusive art scene.

I asked Victoria if she feels hopeful about the future of women in art, and she earnestly shakes her head but explains that there is so much work to be done.

“What shapes the future is not necessarily just what we do now, but how it was conditioned in the past. For change to happen, an enormous amount of effort has to be done and this can only be achieved if everyone works on it, both men and women.”

Group Painting Session in the Drawing Class Foundation

To live as a woman artist is to exist within a paradox: we are continuously forced to participate in the same systems we criticize. Because society forces us to reckon with the politics of privilege and male power, as women, it is easy to fall victim to the illusion of liberation.

Moving forward, to wish for the emancipation of women is to wish for the dismantling of the systems that perpetuate our oppression. Furthermore, women need to understand our culpability for oppression and hold ourselves accountable constantly. It is essential for us to exhaust all means necessary to work towards a future that liberates all artists regardless of gender and background. Even more essential is to forge strong, formidable communities that are fighting for the same thing. After all, as the truism goes: none of us are free until all of us are.

—

Photos and art by the artists of the Drawing Class Foundation. For more information about any of the artworks featured, please contact @drawingclassfoundation on Instagram.

One thought on “Womancipation: Women in Art and the Illusion of Liberation”