So much of a nation’s culture can be explained through its heritage— but in a country like the Philippines where so much pre-colonial history is lost due to colonialism, our past is a safe guess at best.

In an attempt to weave together the threads of our lost pre-colonial history, I reach out to Sharrie Villaver: an artist, costume designer, and pre-colonial culture revivalist, on the challenges of preserving our culture and heritage.

Keeping the gate open

The Philippines has a rich heritage. Our history is equal parts interesting and complicated: a country colonized by the Spanish, the Americans, and the Japanese, before rebranding itself into a republic. However, an oft-disregarded part of our history is on the precipice of dissolution: our pre-colonial past.

When the Spaniards came in 1521, a lot of the existing records pre-colonial Filipinos had were discarded in favor of Catholicism. Most of what we know about pre-colonial Philippines had been passed down orally— with older generations telling stories about the traditions, principles, and practices of pre-colonial Filipinos to the newer generations. Apart from this, the Philippines’ educational curriculum has a limited repertoire of resources about the pre-colonial era, hindering young Filipinos to learn about this part of our history on an academic level.

Despite this, there are individuals and organizations who devote their lives to preserving our pre-colonial heritage.

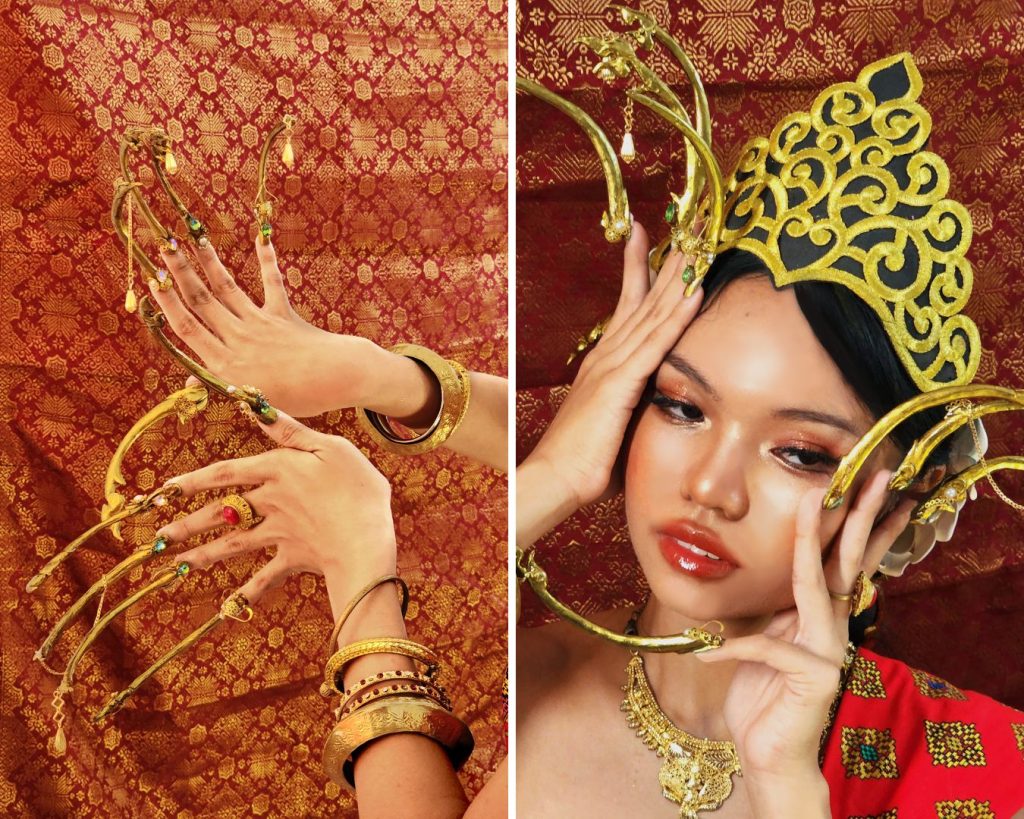

Photo courtesy Kara Salimbangon

One of them is Sharrie Gail Villaver: a freelance artist, illustrator, costume designer, and researcher who specializes in pre-colonial culture. In 2021, Sharrie won the Grand Prize for the University of the Philippines’ system-wide competition for “Cosplaying Filipino History and Folklore”. However, despite the prestigious honor, Sharrie lamented that she had reservations about the nature of the contest.

“I’m just going to be transparent, I didn’t like how they worded it as ‘cosplay’.” Sharrie notes that the term ‘cosplay’ is usually associated with anime or popular culture, not cultural personas. “It might’ve been better to say cultural costume competition or traditional wear competition.”

Sharrie explained that while the event originated in good faith, the lack of information people have about pre-colonialism tends to bleed into how these events are organized. “I appreciate any effort people have in preserving our culture, but we must also put an effort in equipping ourselves with knowledge especially the cultures, traditions, and practices of people [who made these items].”

For the past several years, Sharrie, along with other pre-colonial revivalists, had dedicated themselves to gathering and preserving resources about Filipinos’ pre-colonial way of life so they can be able to share them with more people.

Photo courtesy Jennifer Ann Regidor

Sharrie says gatekeeping has no place in the preservation of these resources. “When you prohibit people from making efforts [in learning about it] this culture is not going to survive. It’s good that even if we’re little in numbers, there are still people who are interested in learning. Right now, what we can do is help spread this information.”

A serendipitous turn of events

Pre-colonial preservation may be a big part of her life now, but it wasn’t always. “It wasn’t a switch button that I pressed to decide that I would devote my life to preserving our heritage.”

In high school, Sharrie was a member of the children and youth choir at Cebu Normal University. Sharrie appreciated that the choir introduced its members to a lot of indigenous songs.“I developed my appreciation for the culture through music and dance because these art forms allowed us to get into the moment and embody our ancestors.”

During her senior high school years, the University of Cebu staged a production that involved pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial narratives— and Sharrie was tasked to be their costume designer. Sharrie admits that when she started researching pre-colonial fashion for this costume design task, a lot of her work was inaccurate, but it was a start.

Photo courtesy Miguel Carlos Bautista

“When I started my research, I saw how beautiful the traditional garments were,” Sharrie was amazed at the craftsmanship of the indigenous textiles. “There weren’t any factories before, so you can only guess that they made all of their garments by hand.”

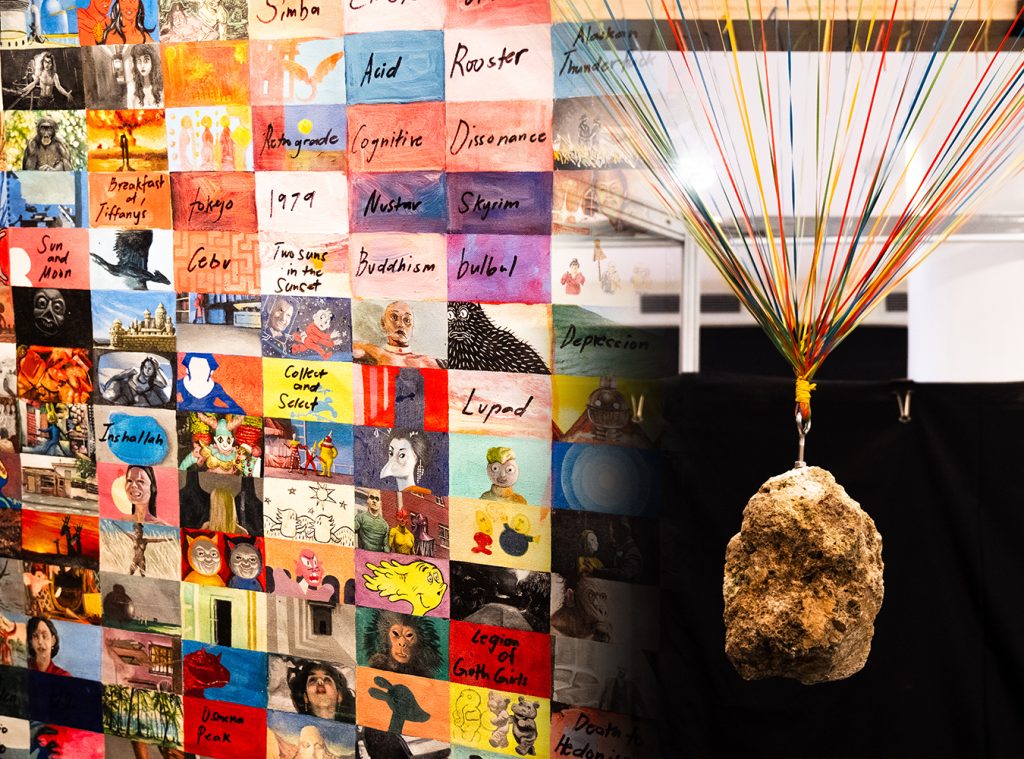

Sharrie’s journey into the world of pre-colonial heritage preservation deepened in college as a Fine Arts student at the University of Cebu. “I became very fascinated by stories about pre-colonial culture, and it showed in my paintings.” Soon, Sharrie became an assistant gallerist at the Jose Joya Gallery, where she was part of a cultural inventory research that involved learning about culture across different regions of the Philippines.

“My main task was researching about ‘intangible heritage’, which was challenging because it’s not artifacts that you can visit and see.” Cebu does not lack in tangible heritage— manifested in the recently concluded Gabii sa Kabilin, an event that promotes Cebuano heritage through touring various museums and heritage sites. However, intangible heritage is a part of cultural heritage that encompasses everything you can’t touch: traditions, beliefs, practices, expression, and even skills that are passed down through apprenticeship.

“Because of the lack of resources here in the Visayas, I have to cross-reference with other sources, which makes me learn about their cultures as well.” Sharrie honed her skills and knowledge through these experiences and continues her work as a pre-colonial culture preserver while doing the things she loves.

With features in local news outlets Sunstar, Cebu Daily News, and more, Sharrie was able to cement herself as a sought-after consultant on pre-colonial fashion and heritage.

Photo courtesy Jennifer Ann Regidor

Piecing together the mosaic of our past, together

The Philippines is an archipelago: which only means that there is so much ground to cover. However, Sharrie isn’t alone in the pursuit of knowledge about our past. She considers her sister, Minxie Villaver, to be one of her mentors and greatest influences.

Minxie is the co-founder of Karakoa Productions and also serves as its creative director, researcher, and lecturer. Sharrie also takes on many roles in Karakoa, as a lecturer, learning facilitator, impressionist, costume designer, and illustrator. Minxie and Sharrie are both representatives for the Visayas for Malaya Saribayan, a cultural empowerment, advocacy, and movement organization that has members from all over the Philippines.

Together, the Villaver sisters hold special webinars where they talk about pre-colonial heritage, practices, and fashion, aiming to promote and preserve it by extending their expertise to other people. Information about these activities can be accessed through Sharrie and Minxie’s personal Instagram accounts.

Despite her creative affinity for pre-colonial heritage, Sharrie says that people do not need to be extensively creative to appreciate it. She cites three ways to better preserve our heritage: Consult, Compensate, and Connect.

Photo courtesy Miguel Carlos Bautista

According to Sharrie, it is deeply important to equip ourselves with knowledge about pre-colonial Filipinos to better understand our national identity. Individuals, organizations, businesses, and event organizers should first consult with experts to improve their events and practices. If there’s anything to learn from Sharrie’s story, it’s that mistakes can and will happen, especially in the beginning. The key to preserving our heritage is a persistent commitment because celebrating our heritage should not be confined to just one month or one day.

Pre-colonial revivalists like Sharrie and Minxie do their work with little to no compensation. To protect and preserve our heritage, it is high time for people in government positions to recognize the valiant contributions of pre-colonial researchers, historians, and revivalists by providing them with financial resources to continue their work.

Most of all, it is extremely important to connect with the community. Collaborating with other organizations that push forward for the preservation of our heritage is important. Sharrie mentions that many young people would be more interested in these activities if they see their peers actively participating as well.

Through the wars we fought and won as a nation, our culture is one that is rife with color and contradictions. Despite it all, learning about our culture and heritage should not be put on the backburner— pursuing real freedom for ourselves comes hand in hand with pursuing justice for our ancestors. We may not achieve it in full during this lifetime, however, with our collective efforts, we can come to something close. After all, how else could we hope for a better future if we don’t learn from the lessons of the past?